The History of School Lunches in the United States

Think of school lunches today, and visions of colorful trays loaded with pizza slices, fresh fruit, and cartons of milk come to mind. The real story of school lunches in the U.S., though, is one of resilience, innovation, and a continuing quest to make sure that children get the nutrition they need to flourish. This more-than-a-century-long journey reveals some fascinating shifts in how schools fed millions of children.

The Humble Beginnings: 1800s Experiments

The idea of feeding children at school didn’t originate in the United States but in Europe. In 1790, Benjamin Thompson, an American-born physicist also known as Count Rumford, introduced mass-feeding programs in Munich, Germany. His soup kitchens served nutrient-rich meals of potato, barley, and pea soup—a filling and economical solution to hunger.

In the U.S., the first recorded effort to feed schoolchildren took place in 1853 when the Children’s Aid Society of New York began serving meals at a vocational school. However, the idea didn’t catch on nationally until later, remaining an experiment confined to major cities.

Early Local Programs: Penny Lunches and Community Efforts (1890s–1920s)

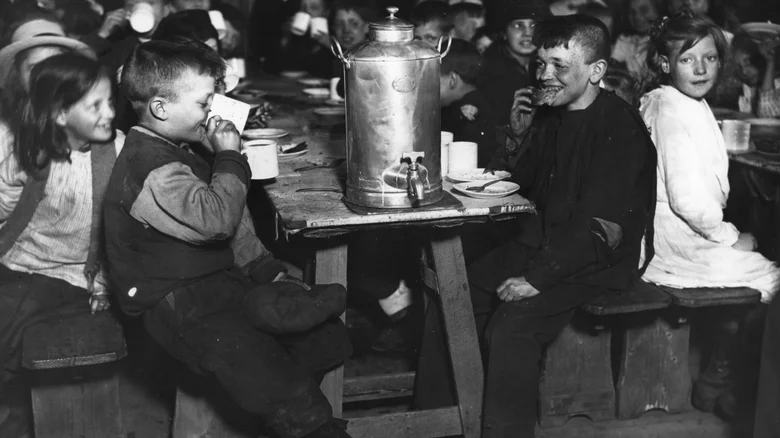

In the 1890s, cities like Philadelphia and Boston introduced “penny lunches,” where children could buy a meal for just one cent. These lunches were often served in church basements or small kitchens near the schools and featured simple but hearty foods.

- Philadelphia (1894): The Starr Center Association launched its penny lunch program by serving hot soup and bread. The program expanded to nine schools, offering meals like stewed beans, macaroni, and milk.

- Boston (1908): The Women’s Educational and Industrial Union ran a central kitchen that transported hot lunches to multiple schools. A typical meal might include beef stew, an apple, and whole-grain bread.

In many of these programs, lunches were prepared by volunteers or home economics students learning valuable cooking and budgeting skills.

Fun Fact: In some schools, children ate at their desks due to a lack of lunchrooms. This early format paved the way for the cafeteria-style dining that became popular later.

The Great Depression and Federal Aid (1930s)

The Great Depression of the 1930s marked a turning point for school lunches. As unemployment soared and poverty deepened, millions of children came to school hungry. Teachers noticed that hunger affected attendance, behavior, and academic performance. Parent-Teacher Associations (PTAs) and local charities organized school feeding programs to combat this issue.

- Government Assistance (1935): Public Law 320 provided funds for surplus agricultural goods like butter, potatoes, and cheese to be distributed to schools. This approach supported both struggling farmers and malnourished children.

- Typical Meals: Menus often featured vegetable soup, baked potatoes, and cornbread. In some schools, cocoa and biscuits were served during winter months.

In rural areas where school kitchens were scarce, teachers improvised. The “pint jar method” became common: children brought soups or cocoa in glass jars, which were heated in buckets of water placed on classroom stoves.

The Birth of the National School Lunch Act (1946)

After World War II, Congress recognized that child nutrition was a matter of national security. Many draftees during the war had been rejected due to health issues linked to poor childhood nutrition. In response, President Harry Truman signed the National School Lunch Act in 1946.

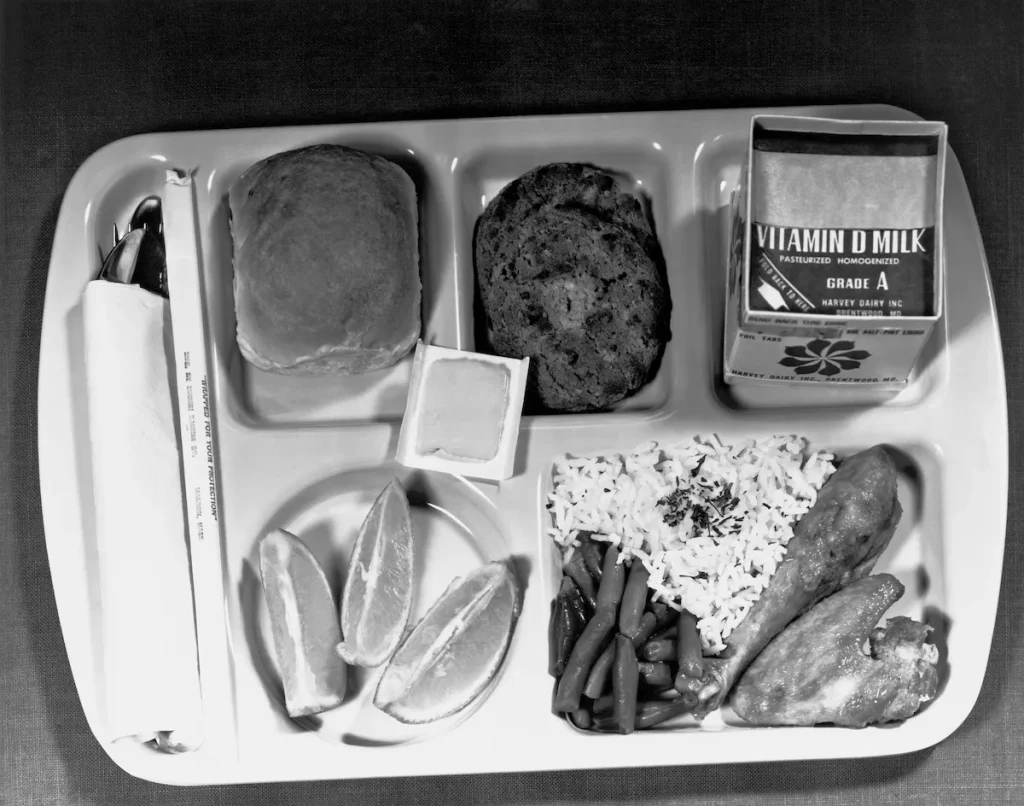

This Act created a permanent, federally funded program aimed at providing balanced meals to schoolchildren. Schools were required to serve Type A lunches, which included:

- Protein: Meat, poultry, fish, cheese, eggs, or peanut butter.

- Vegetables/Fruit: At least three-quarters of a cup.

- Bread or Whole Grains: One serving.

- Milk: A half-pint.

A typical lunch might include a serving of meatloaf, green beans, buttered bread, a baked apple, and milk. These meals were designed to provide one-third to one-half of a child’s daily nutritional needs.

Historical Note: Some schools still lacked adequate kitchens or cafeterias in the late 1940s, so many lunches were prepared at home by volunteer groups and transported to schools.

Expansion and Civil Rights (1950s–1960s)

During the Civil Rights era, efforts to ensure fair access to school lunches gained momentum. The federal government increased funding to improve kitchen facilities and ensure low-income children had access to free or reduced-price meals.

- Regional Variations: Southern schools often served cornbread, collard greens, and fried chicken. In contrast, Midwestern schools featured hearty casseroles and beef stew.

- Mobile Cafeterias: In rural areas, mobile food trucks known as “kitchen buses” delivered hot meals to schools without kitchens.

Key Development: In 1966, the Special Milk Program expanded to provide free milk to children in schools and childcare centers, emphasizing nutrition even outside of lunch hours.

The Nutrition Reform Era (1970s–1980s)

The 1970s and 1980s brought new challenges, as rising childhood obesity rates prompted a shift in focus from calories to food quality. The USDA introduced guidelines to reduce sugar and fat while increasing fresh fruits, vegetables, and whole grains.

- Lunch Menus: Instead of heavy, starchy foods, lunches began to include baked chicken, salads, and fresh fruit cups.

- Fast Food Influence: The 1980s saw the introduction of convenience foods like pizza and chicken nuggets, which were quick to prepare but often criticized for their nutritional content.

The 21st Century: Health, Diversity, and Modernization

The 2010 Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, championed by First Lady Michelle Obama, introduced stricter nutritional guidelines. Schools were required to offer more fresh produce, limit sodium, and provide whole grains.

- Cultural Inclusivity: School lunch menus began to reflect diverse cultural preferences, offering options like tacos, stir-fries, and vegetarian dishes.

- Farm-to-School Programs: Many schools partnered with local farms to source fresh ingredients, offering students seasonal fruits and vegetables.

In addition, technology has transformed the school lunch experience. Digital meal ordering systems and cafeteria apps now allow students to customize their meals and track nutrition.

Memorable School Lunches Through the Decades

- 1920s: Bowls of bean soup with a slice of rye bread.

- 1940s: Meatloaf with mashed potatoes, string beans, and milk.

- 1960s: Chili con carne, cornbread, and fruit cobbler.

- 1980s: Chicken nuggets, apple slices, and chocolate milk.

- Today: Quinoa bowls with roasted vegetables and fruit smoothies.

The Legacy of School Lunches

School lunches have evolved from penny stews served in church basements to balanced, culturally diverse meals prepared in modern cafeterias. This evolution reflects broader social changes, from fighting hunger and poverty to addressing health and wellness. However, the core mission remains the same: to nourish children so they can learn, grow, and thrive.

The story behind the lunch tray is one of creativity, community, and care—an enduring symbol of how a simple meal can support the future of a nation.