Ancient Bread: The Kalach

For centuries, one of the simplest yet most beloved snacks in Russia was the kalach—a bread so ingeniously designed that you could eat it anywhere. Shaped like a loop with a “handle,” it was made to be held with unwashed hands while the bread itself stayed clean. After finishing the soft, pillowy center, the “handle” could be thrown away, fed to animals, or, in times of hunger, eaten in full.

The kalach is a cultural symbol, embedded in the folklore, rituals, and history of Eastern Europe. But how did this unique loaf become a cornerstone of Russian tradition? Let’s take a journey through its origins, spread, and enduring legacy.

The Origins of Kalach: Bread with a Handle

The name “kalach” has a few possible origins. One theory traces it to the word “kolo,” meaning “circle,” reflecting its round shape. Others suggest it comes from the verb “kalit,” meaning “to bake,” or from a Turkic word for “ear.” The most intriguing origin theory is that kalach arrived with the Tatar-Mongols in the 12th and 13th centuries, blending Russian and Tatar baking traditions.

Murom, a small Russian city on the banks of the Oka River, claims to be the birthplace of this bread, a point marked by the presence of kalach on its coat of arms and even a monument in its honor.

The earliest recorded kalach dates back to this city in the 14th century. This was a time of simple yet hearty bread, often made from rye. However, the introduction of white wheat flour, adapted from Tatar baking traditions, changed Russian breadmaking. By adding sourdough starter—traditionally used for rye bread—to wheat flour, bakers created a festive, highly prized loaf that rose high and remained fresh for weeks.

The kalach wasn’t an everyday loaf. It was a luxury item, reserved for special occasions like religious feasts and celebrations. Its symbolic shape—a thick middle section with a thinner loop resembling a “castle” or “wishbone”—was as iconic as its soft, tender crumb.

A Loaf Worth Protecting: Kalach in Russian Folklore

In his famous book Moscow and Muscovites, historian Vladimir Gilyarovsky painted a vivid scene of 19th-century Moscow life. He described a chaotic moment when a runaway carriage overturned a sewage worker’s barrel, spilling its contents across the street. Despite the disaster, the worker’s main concern was keeping his kalach safe. He held it high above his head, determined to keep it clean—a humorous but telling anecdote that demonstrated how cherished this bread was.

The significance of kalach wasn’t limited to street food. At merchant tables, kalach was often a marker of status. Wealthy hosts would serve the soft middle section while discarding the handle. If a family began eating the entire loaf—including the handle—it was seen as a sign of financial hardship. This practice gave rise to the Russian saying “doyti do ruchki” (literally, “get to the handle”), meaning to fall on hard times or hit rock bottom.

A Culinary Journey Across Time

The spread of kalach throughout Russia was closely tied to the expansion of the Moscow Principality. After Murom was annexed in the 14th century, kalach recipes spread to bustling city markets. By the 1500s, Novgorod scribes noted the presence of professional kalach bakers in faraway towns like Korela (modern-day Finland). The bread’s popularity surged when Tsar Ivan the Terrible served kalaches alongside fish and kvass during a funeral banquet for Prince Konstantin in 1559.

During the 17th century, kalaches became grander in scale. Author Grigory Kotoshikhin described massive birthday kalaches that could be two or three arshins long (up to 7 feet!) and thick enough to be cut into dozens of slices.

Kalach frequently appears in the works of famous writers. For instance, it is mentioned in Korney Chukovsky’s autobiographical story “The Silver Emblem,” Ivan Bunin’s autobiography “The Life of Arsenyev,” Alexander Kuprin’s novel “The Yunker,” Maxim Gorky’s “The Life of Klim Samgin,” Leo Tolstoy’s “Anna Karenina,” and Fyodor Dostoevsky’s “The Devils.”

It is a shame that the kalach is really no longer as available as it was. It began disappearing from shelves in the 1960s, and by the early 1970s it was mostly gone completely, except in specific regional shops or on menus. Today it is making a soft comback.

The Art of Making Kalach: An Ancient Craft

Baking a kalach was no simple task. The dough was made using high-grade flour, which was sifted several times to ensure an ultra-fine texture. The flour was mixed with water, yeast, and salt, then allowed to rise multiple times. Each rise and kneading cycle strengthened the dough, creating the signature airy texture and springy crumb.

The dough was prepared on special icy tables, kept cold with containers filled with ice to ensure the surface remained chilled. This cold kneading technique, where the dough was rubbed against the icy surface to prevent overheating, gave the bread its distinct firm and elastic texture. These kalachs were called tertye (rubbed), and the phrase “no rub, no knead—no kalach” became a metaphor for how hardship and effort often lead to valuable outcomes. Over time, a determined or resilient person was nicknamed a terty kalach—a “seasoned” individual.

Another hallmark of kalach was the slit, or guba (lip), running along its belly. This slit allowed carbon dioxide to escape during baking, preventing the bread from bursting. To keep it from sticking in the oven, the guba was dusted with flour. Once baked, it could be peeled back and filled with honey, butter, or other spreads. This practice inspired the Russian saying “to roll the lip,” meaning to want or expect too much. Before baking, the kalaches were dusted with flour, sprayed with water, and placed on a heated tray inside a scorching-hot oven (often reaching 250–270°C or 480–515°F). The rapid bake time—usually around 10 to 15 minutes—created a light, golden crust that barely browned, preserving the soft, pillowy interior.

Crafting kalach was no easy feat. From the icy tables and cold fermentation to the finely milled flour, it required expertise and tools that few households possessed. As a result, kalach was rarely baked at home and instead sold at specialized “kalach rows.” These stalls were kept far from residential areas to avoid the bread absorbing unpleasant odors. Because of the skill and cost involved, kalach became a luxury that only the wealthy could afford. Those from humbler backgrounds who wandered into a kalach row were easily spotted and quickly shown out, giving rise to the phrase “with a pig’s snout and into the kalach row”—a colorful way of saying someone was out of their depth.

The secret to kalach dough lay in its ability to stay fresh for an extended period. In the 19th century, kalaches were even frozen in Moscow and transported by coach to Paris, where they were thawed in warm towels and served as if freshly baked—a testament to their remarkable preservation.

Kalach Across Eastern Europe: A Symbol of Celebration

The concept of kalach wasn’t exclusive to Russia. Variants of this bread appeared throughout Central and Eastern Europe, often playing key roles in religious and cultural traditions:

- Ukraine: The Ukrainian kolach is braided and typically served during Christmas Eve’s Holy Supper. Stacked in sets of three to symbolize the Holy Trinity, it represents eternity and unity.

- Poland: The Polish kołacz is a circular bread sometimes filled with sweet ingredients like poppy seeds, cheese, or dried fruit. Lavishly decorated versions called korovai are used at weddings as symbols of prosperity.

- Hungary: The Hungarian kalács is a sweet, braided bread similar to brioche and traditionally associated with Easter. It is often consecrated in church alongside ham and served during holiday feasts.

- Romania and Moldova: The colac is a braided loaf made for special occasions like Christmas, weddings, and funerals. Groups of carolers often receive colaci as gifts during holiday visits.

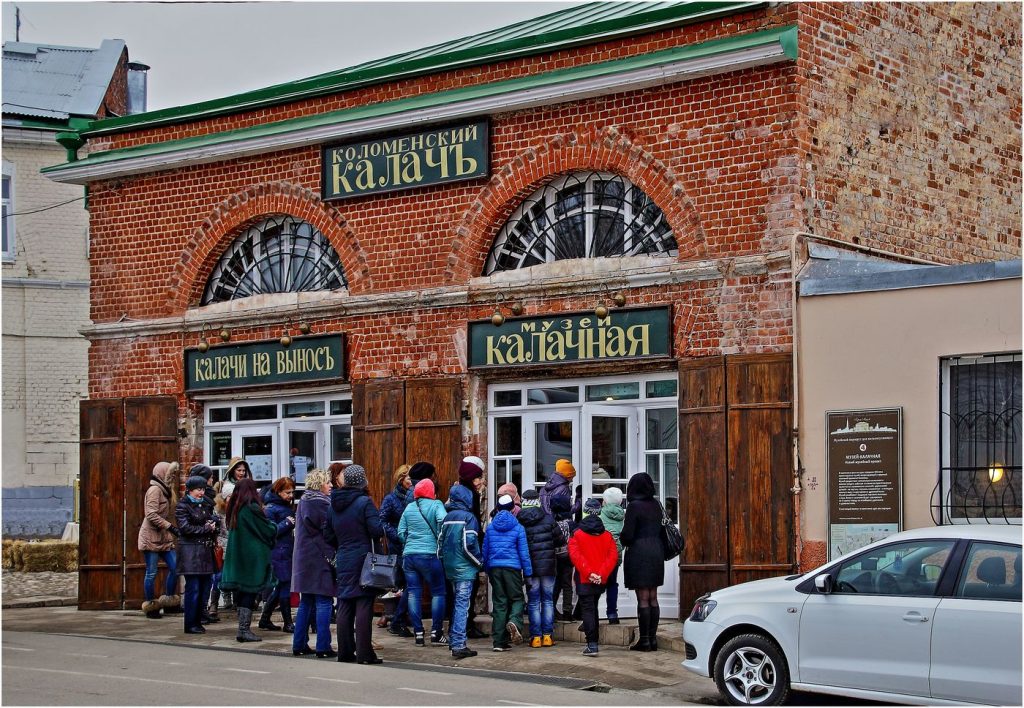

Preserving Tradition: The Kalach Museum in Kolomna

In Kolomna, a historic town 120 kilometers south of Moscow, the Kalach Museum keeps this tradition alive. Visitors can learn about the history of kalach while baking their own loaves in a traditional Russian stove. They’re taught the importance of using ultra-fine flour and keeping the dough cold during kneading—a technique involving ice drawers beneath the counter.

Bake Your Own Kalach: A Taste of History

Curious to try this historic bread at home? Here’s a classic kalach recipe for you to bake.

Ingredients (for 4 loaves):

- 450g high-grade flour (12-14% protein) + 80g for dusting

- 320g water

- 6g fresh yeast

- 8g salt

Instructions:

- Dissolve the yeast and salt in water. Add the flour and knead the dough until smooth.

- Cover the dough and let it rise at room temperature for 4 hours, punching it down every hour.

- After the final kneading, refrigerate the dough for 2.5 hours.

- Divide the dough into 4 pieces, shape into balls, and rest for 15 minutes.

- Form each ball into a loop, joining the ends to create a handle.

- Proof for 30-40 minutes.

- Preheat the oven and baking tray to 250°C (480°F). Spray the dough and oven walls with water.

- Bake for 10-15 minutes until the crust is set but not overly browned.

Enjoy your kalach warm—perhaps with a spread of duck pâté or butter—and experience a slice of history in every bite.