Kale, Chorizo, and Memory: The Enduring Magic of Portuguese Soup

I first tasted this soup in November 2016, a time when everything in my life seemed to be shifting at once. Personally, professionally, even politically—the world felt unsteady. Our family had just made the difficult decision to close our beloved Bear restaurant in New York City. After eleven years of working, studying, and building a life there, it was time to leave.

In the middle of all that chaos, we did the only thing that felt right—we got in the car and drove. My sister, her partner, their two poodles, and I set off for Provincetown, hoping to find a little space to breathe, a little quiet before the next chapter in our lives.

The drive was long, and we’d stop every once in a while, to let the dogs out, and to look at the hills and landscapes of New England. New York City faded far into the distance of time and space, as we drove silently, looking at the passage of towns and lakes and clouds outside.

I’ve only ever known Provincetown in November. By then, the summer crowds have long since vanished. The beaches are empty, the ocean is sharp and dark, and the wind cuts through Commercial Street like a blade. The sun shines bright in the mornings, the cold sand brimming, the oysters tanning on the shore, but it disappears early, swallowed by an endless black sea. A few restaurants and bars stay open, their glow welcoming the last of the lingering tourists, but mostly, it’s just locals.

In November Provincetown is a completely different place, and exactly what we needed.

We stayed at a bed and breakfast run by a couple who had lovingly restored the place themselves. Every morning, one of the owners would set out freshly baked muffins and cookies near the kitchen. In the evenings, we drank wine and stayed up late talking with the other guests, sometimes gathering around the kitchen table with takeout from the local Chinese spot. The whole experience was small, intimate, and strangely comforting.

But the highlight of that trip—maybe the thing that stayed with me the most—was the soup.

It happened at the Lobster Pot, a legendary Provincetown institution. I ordered the Portuguese soup on a whim, not expecting much. But from the first spoonful, something clicked.

This hearty kale soup, brimming with greens, potatoes, spicy sausage, and beans, has become a staple for locals and visitors alike. Often simply called “Portuguese soup” on the menu, it represents both a delicious comfort food and a living piece of Cape Cod’s multicultural heritage. Anthony Bourdain, returning to Provincetown decades after his first cooking job, famously savored a bowl at the Lobster Pot and declared it “just what I remembered,” loaded with “kale, fiery red chorizo, linguiça, kidney beans, [and] potatoes”.

Yes, the lobster was fantastic. Yes, the stuffed cod was incredible. Yes, the drinks were strong. But that soup? That soup was something else.

We ate at the Lobster Pot every day, sometimes twice. But in the mornings I’d walk there alone. The moment they opened, I’d order a Portuguese soup to go. It became a ritual. I craved it, needed it. Something about it nourished me in a way I couldn’t explain.

The whole town felt that way—restorative, in a quiet, eerie kind of way. The cold ocean air, the near-empty streets, the warm meals in dimly lit restaurants. The whales playfully dipping themselves out of the freezing waters in the distance.

Walking along the dunes, in that crazy wind that over years had bent trees to its fierce will, I thought about the last few years of my life, the friendships and relationships, the failures and the successes, and the city I was leaving behind into an unknown future. There was something both haunting and welcoming about it all. I hadn’t realized how exhausted I was, how exhausted we all were. I hadn’t really taken a break from the moment I moved to New York City when I was 22 years old, and now here I was eating brown soup and standing at the edge of the world somewhere. I think the restorative nature of that soup and that town, healed me from whatever was languishing in me. There’s something special there, some magic in that air.

A Hearty Heritage: Portuguese Soups and Provincetown’s Community

The presence of Portuguese kale soup in Provincetown is no coincidence – it’s a direct result of the town’s rich Portuguese heritage. Beginning in the mid-19th century, waves of immigrants from Portugal (especially the Azores islands) arrived in Provincetown, drawn by booming whaling and fishing industries.

Many Azorean fishermen were recruited as crew for New England whaling ships and later settled with their families at the Cape’s tip. By the late 1800s, Portuguese immigrants comprised a substantial portion of Provincetown’s population and dominated its fishing fleet. Along with their seafaring skills, these families brought their Catholic faith, cultural traditions, and of course their cuisine – including a love of hearty soups.

One of the most enduring dishes they introduced was caldo verde, the famed “green broth” soup of northern Portugal made with kale (or collard greens), potatoes, and sausage. In Provincetown, this evolved into what locals simply call “kale soup” or sopas de couve.

In fact, old-timers in P-town refer to kale itself as couves – the Portuguese word for cabbage – since the leafy kale was a staple green in their kitchens. Portuguese kale soup quickly became a staple of immigrant households from the late 1800s onward, with huge pots simmering to feed large fishing families for days. It was economical, nourishing, and easy to stretch – packed with garden vegetables, potatoes, beans, and a bit of cured meat for flavor. Over time it earned the affectionate nickname “Portuguese penicillin,” regarded as a cure-all comfort food much like chicken soup in Jewish tradition.

As the Portuguese community grew and interwove with the Cape’s culture, their beloved soup became as common on local menus as New England clam chowder.

In towns with significant Portuguese populations like Provincetown and nearby Fall River, you can find kale soup at least as easily as a cup of chowder. Provincetown’s annual Portuguese Festival and Blessing of the Fleet celebration each summer highlights the community’s traditions, from colorful parades to food events celebrating dishes like kale soup and sopas (a bread-and-meat soup served at Azorean Holy Ghost feasts). In short, Portuguese soups have become part of the broader Cape Cod culinary landscape, treasured by Portuguese-Americans and “washashores” (newcomers) alike.

The Lobster Pot: A Cape Cod Institution with Portuguese Roots

At the heart of this story is the Lobster Pot, a waterfront restaurant on Commercial Street that has been serving hungry patrons for over 70 years. The Lobster Pot first opened in 1943 under Portuguese-American owners Ralph and Adeline Medeiros.

Ralph Medeiros had arrived from a nearby Portuguese community and, with his wife, started the restaurant in a humble former tavern building during World War II. From the beginning, the menu likely reflected a blend of Cape Cod seafood and the Portuguese flavors common in local homes. The Medeiros family ran the Lobster Pot until 1979, when they sold it to the McNulty family – who vowed to preserve the restaurant’s authentic Cape Cod character.

Under Joy McNulty and later her son, chef Tim McNulty, the Lobster Pot not only continued to thrive but also maintained a strong connection to Provincetown’s Portuguese culinary heritage. In addition to the famous lobster dishes and chowder, the menu features “Portuguese specialties” like the kale soup and a baked stuffed cod with Portuguese sausage.

Generations of visitors have come to expect a cup of Portuguese soup as much as a lobster roll. In fact, the Lobster Pot’s own 2010 cookbook notes that their most popular menu item – the classic Lobster Pot Clambake platter – traditionally includes a choice of soup: clam chowder, lobster bisque, or Portuguese kale soup, alongside the steamed shellfish and corn. The restaurant’s bright neon sign and welcoming bowls of soup have guided countless people in from the cold Provincetown winds since the mid-20th century.

The Lobster Pot has also played an active role in the community, sponsoring local events and honoring the town’s heritage. The McNultys have been involved in the Provincetown Portuguese Festival over the years, helping to keep those traditions alive.

It’s no wonder that when Anthony Bourdain returned to P-town for his CNN Parts Unknown episode, he made a beeline for the Lobster Pot – calling it one of the last holdouts of “old Provincetown” and praising it for still serving “what I want and need – the essentials,” namely that Portuguese soup he craved. In his words, it was “the P-town version of the Azorean caldo verde, and just what I remembered”. The Lobster Pot, by keeping dishes like kale soup on the menu, has essentially become an unofficial ambassador of Portuguese-American cooking on Cape Cod.

Portuguese Kale Soup: Ingredients and Regional Variations

So what exactly is in this famous Portuguese soup? At its core, Portuguese kale soup is a hearty mélange of greens, beans, and cured pork in a savory broth. The Lobster Pot’s version (and most Cape Cod variants) typically includes: kale (the star green), potatoes, linguiça and/or chouriço sausage, beans (often red kidney beans), along with onions, garlic, and broth. Bourdain described it succinctly as “kale, fiery red chorizo, linguiça, kidney beans, [and] potatoes” in a steaming bowl. The combination yields a soup that is warming, filling, and packed with flavor – slightly smoky and spicy from the sausage, earthy from the kale, and silky from the starchy potatoes.

That said, there are countless variations on Portuguese kale soup, both within Provincetown and across the Portuguese diaspora. It seems every cook has a unique spin. Some differences can be traced to regional origins: families from different Azorean islands or mainland Portugal have their own traditions. For example, Azorean-influenced recipes (common in Provincetown) often rely on linguiça – a smoked Portuguese pork sausage seasoned with garlic and paprika – as the primary meat, whereas some mainland Portuguese recipes might use larger chunks of fresh pork or ham alongside or instead of sausage. In Provincetown’s early days, many cooks would throw in whatever protein was available – a ham bone, a smoked shoulder, or leftover pork – to enrich the soup, stretching it into multiple meals.

Beans are another point of variation. Some traditionalists use dried white pea beans (navy beans), which was the choice of legendary Cape Cod chef Howard Mitcham in his recipe, while others (like Bourdain) prefer red kidney beans for color and heft. Still others shortcut the process – one celebrated local cook, Ruth O’Donnell, notes that she eventually began adding a can of Campbell’s bean-and-bacon soup to her kale soup instead of cooked beans, for convenience and a flavor boost. Both linguiça (which is usually mildly spicy) and chouriço (a similar sausage that is often spicier and cured a bit differently) can be used; some cooks include both for complexity. The Lobster Pot’s soup uses a mix of sausage – a tradition in Provincetown – whereas one longtime Portuguese restaurant in town, The Moors (operating since 1939), makes their “Portuguese soup” using only chouriço and notably substitutes cabbage for kale. The Moors’ version is a reminder that “kale soup” can be interpreted loosely; their recipe opts for chopped cabbage, carrots, and tomatoes simmered with chouriço and kidney beans – a variation on the theme that still delivers a hearty Portuguese-style soup.

Tomatoes, carrots, and other vegetables are yet another area where recipes diverge. Purists in Provincetown, like some Azorean matriarchs, scoff at adding things like tomato, carrot, wine, or garlic – insisting that a basic kale, potato, meat, and water approach is the authentic method. On the other hand, many cooks happily enrich their soup with extra ingredients as they became affordable. It’s not uncommon to see tomato added for a touch of sweetness and acidity, carrots for color, or a splash of red wine or vinegar to brighten the broth. One local recipe handed down in the Raposo family is considered unusual because it includes stew beef in addition to linguiça, simmering chunks of beef for hours to make an extra-rich soup. Clearly, Portuguese kale soup is a flexible canvas – as a Provincetown cookbook notes, the soup “is forgiving and can take the addition of just about anything,” though the best versions tend to keep it simple at heart

Despite all these variations, the common denominator is the soul-satisfying quality of the dish. Proper Portuguese kale soup should be thick with ingredients – almost a stew – and boldly flavored. The kale (traditionally collard greens in Portugal proper, but often curly kale in New England) gives the soup its nourishing green goodness. The potatoes, usually cut into chunks, may partially break down to naturally thicken the broth. The sausages infuse smoky, garlicky warmth throughout the pot, their red paprika-tinged oil giving the broth an appetizing reddish hue. And whether you bite into a piece of linguica or scoop up a tender bean, every spoonful provides sustenance. No wonder Cape Codders swear a bowl of this soup can “cure what ails you” it’s practically a meal and medicine in one.

Cooking Methods: Traditional and Modern Preparations

Traditional Preparation

The old-fashioned way to make Portuguese kale soup is slow and steady. Historically, a Portuguese fisherman’s wife might start a large cauldron of kale soup in the morning and let it simmer for hours while tending to other chores, letting the flavors deepen over time. Dried beans would be soaked overnight and cooked with a ham hock or pork bone to create a flavorful stock base. After skimming the broth, the hearty ingredients – chopped kale, potatoes, linguiça or chouriço (often homemade or from a local butcher) – would be added and gently simmered until tender. Many recipes call for a long cooking time: one famous version by Howard Mitcham insists on at least five hours of simmering for the best flavor. The result is a soup that only improves with time; as one recipe notes, this soup “gets better each day” when reheated, as the ingredients mingle. Traditionally, nothing would go to waste – if a garden yielded extra turnips or a bit of cabbage, into the pot they went. Before serving, the cook might taste and adjust seasoning (salt, pepper, perhaps a pinch of red pepper flakes for heat) and often let the soup cool and reheat it, as that second warming could meld flavors even more.

A key traditional technique is rendering the sausage. Linguiça and chouriço are fatty sausages, and many cooks like to sauté or broil them separately first to release some of their fat (and to brown them for extra flavor). For instance, one local method is to lightly broil the linguiça before adding it, charring the edges and removing excess grease, so the soup doesn’t become overly oily. The browned bits of sausage can then be added towards the end of cooking, ensuring their flavor permeates the soup without all the fat. Similarly, garlic and onions are typically sautéed at the start of cooking in a bit of olive oil or pork fat (like salt pork), which provides the aromatic foundation of the soup.

Modern Adaptations

Today, home cooks might take some shortcuts but still aim for authentic flavor. It’s common to use canned beans instead of dried, drastically cutting down preparation time (you can add drained canned kidney or navy beans directly to the soup in the final stages). Store-bought chicken or beef broth can replace a home-simmered ham bone stock if one is short on time. Some contemporary recipes, including one published by Yankee Magazine, replace hard-to-find ingredients with easier substitutes – for example, if linguiça is unavailable in your area, you can swap in a spicy smoked sausage like kielbasa or even Spanish chorizo. Fresh kale (curly or lacinato) is often available year-round, but frozen kale or even collard greens can be used in a pinch, as one local recipe does.

Modern chefs also play with flavor boosters that old Portuguese grandmothers might not have used. Anthony Bourdain’s take on the soup in his cookbook Appetites includes a dash of red pepper flakes and a tablespoon of sherry vinegar at the end for a subtle kick and brightness. Others squeeze in a bit of lemon juice (as the classic Joy of Cooking recipe suggests) to wake up the flavors just before serving. These additions balance the richness of the sausage and potatoes with a touch of acid. Yet, even with such tweaks, the core method remains true to tradition: a one-pot slow simmer to marry robust ingredients. Whether cooked on a modern stovetop or in a slow-cooker, the goal is to achieve that time-honored depth of flavor.

One thing that hasn’t changed is how the soup is served. Portuguese kale soup is best enjoyed piping hot, preferably with a chunk of crusty bread on the side for dunking. (In Provincetown, that might be a slice of locally baked Portuguese sweet bread or cornbread, or even a malasada “flipper” on the side, per tradition.) It’s a humble dish meant to feed a crowd, so it’s often served in generous bowls as a starter or even a main course. In the Lobster Pot’s bustling dining room, you’ll see cups of kale soup landing on tables alongside oyster crackers and Portuguese rolls, feeding multitudes just as it did a century ago in fishermen’s cottages.

The Lobster Pot’s Portuguese Soup in the Spotlight

Over the years, the Lobster Pot’s Portuguese soup has garnered praise from food critics and everyday diners alike. It’s frequently lauded in travel guides and reviews – “Best Portuguese Kale Soup… EVER!!” raves one TripAdvisor reviewer.

Its reputation grew beyond Provincetown when celebrity chefs and writers took note. Anthony Bourdain’s on-air endorsement in Parts Unknown (2014) is perhaps the most famous shout-out, where he nostalgically relished the soup as a taste of his youth in P-town.

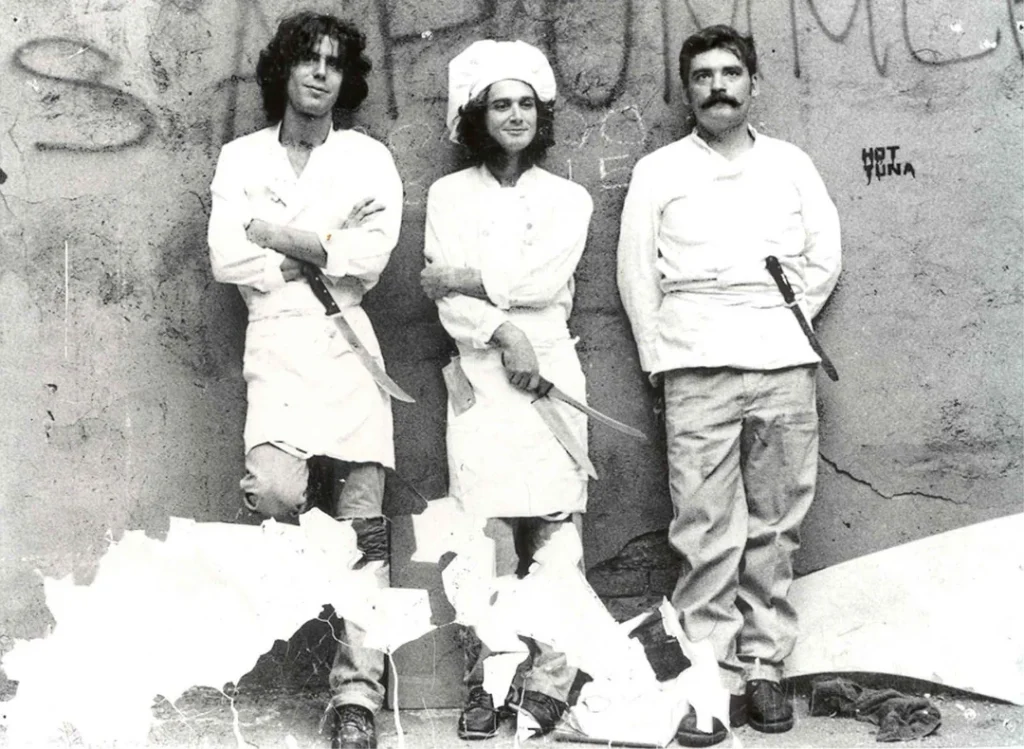

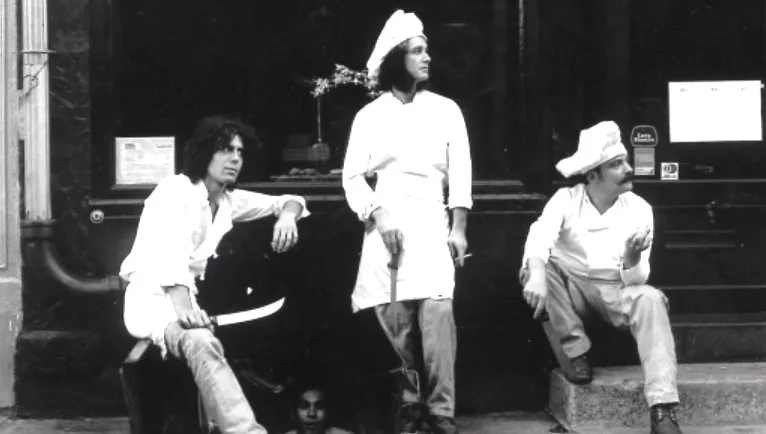

Bourdain’s enthusiasm was rooted in personal history: as a young cook in the 1970s, he had lived and worked in Provincetown (his first kitchen job was actually washing dishes and shucking clams at another local spot, but he and his friends often ate around town).

Tucking into the Lobster Pot’s kale soup decades later, Bourdain found it unchanged and just as comforting – a testament to the restaurant’s consistency and respect for tradition. He noted that this Portuguese soup was “precisely what I loved about the food here – the Portuguese thing” that sets Cape Cod cuisine apart.

Local chefs also acknowledge the importance of the dish. Chef Tim McNulty of the Lobster Pot grew up surrounded by Provincetown’s Portuguese flavors (his mother Joy even helped sustain the town’s Portuguese Festival), so it’s natural that he carried on with recipes like the soup and a Portuguese-style stuffed cod on the menu

In the Provincetown Portuguese Cookbook, Chef Tim contributed a recipe for “Portuguese Codfish” baked with a linguiça stuffing, showing how Portuguese ingredients feature in the Lobster Pot’s creations beyond just the soup.

Food writers have also documented the soup’s lore: Laura Siciliano-Rosen, writing for Eat Your World, noted that on Cape Cod this soup is “a must-eat dish with local history,” tracing from Minho, Portugal to New England, and that her first taste of a home-cooked version (after many restaurant bowls) was a revelation on a cold winter day.

Through such accounts, one begins to appreciate that the Lobster Pot’s Portuguese soup is more than just a menu item – it’s a symbol of Provincetown’s unique blend of cultures. It links the past to the present in a very tangible (and tasty) way. Each bowl served at the Lobster Pot carries forward the legacy of those Azorean grandmothers who brought their recipes to Cape Cod, the fishermen who needed a hot meal after a damp day at sea, and the generations of locals who refuse to let that heritage fade. The restaurant, by keeping this soup on its tables, honors the Portuguese community that is so integral to Provincetown’s identity. As long as the Lobster Pot ladles out Portuguese kale soup, a piece of Provincetown’s soul is kept alive and well.

Recipe: Provincetown Portuguese Kale Soup (Lobster Pot Style)

Ready to try this delicious soup yourself? Below is a detailed step-by-step recipe inspired by the Lobster Pot’s version and traditional Provincetown Portuguese cookery. It includes ingredient sourcing tips and modern conveniences without sacrificing authenticity. This makes a generous pot of soup (about 8–10 servings), perfect for a family meal or freezing for later – and yes, it tastes even better the next day!

Ingredients:

- Kale: 1–2 bunches of fresh kale (about 1 pound), preferably curly kale. Wash well, remove the tough center stems, and coarsely chop the leaves. Tip: You can substitute collard greens or even use frozen chopped kale if fresh is unavailable. In a pinch, cabbage can be used for a slightly different but still authentic result (one Provincetown restaurant uses cabbage instead of kale). Source.

- Linguiça sausage: ~1 pound, sliced into 1/4-inch thick rounds. Tip: If you can find Portuguese linguiça (a smoked garlicky pork sausage) or chouriço, use it for the most authentic flavor. Many New England grocers carry it, and it’s available online. If not, substitute a similar smoked sausage – a spicy kielbasa or Spanish chorizo can work well. Using a mix of sausage types (half linguiça, half chouriço) is ideal, as done in some Cape Cod recipes.

- Ham hock or bacon (optional): 1 large ham hock or a 4-ounce chunk of salt pork or slab bacon. This will flavor the broth with smoky depth. If unavailable or if you prefer less pork, you can omit this, especially since the sausages are quite flavorful on their own.

- Onions: 2 medium onions, chopped.

- Garlic: 2–3 cloves, minced.

- Potatoes: 3–4 large potatoes (about 1.5 pounds total), peeled and cut into bite-sized chunks. Yukon Gold or red potatoes hold their shape well; Russets can be used but will break down more (thickening the soup).

- Beans: 2 cups cooked beans (from about 1 cup dried) – traditionally red kidney beans or white navy beans. Tip: You can use one 15-oz can of beans, drained and rinsed, for convenience. Kidney beans will give the soup a classic look (the red beans against green kale), while small white beans are equally authentic (Howard Mitcham used navy beans.

- Tomatoes (optional): 1 cup of crushed tomatoes (canned) or 2 tablespoons tomato paste. Not all recipes use tomato, but a bit can enrich the broth and is used in some Provincetown versions (and won’t be frowned upon except by the strictest purists). This is optional.

- Carrots (optional): 1–2 carrots, sliced. (Also optional; include if you like a slightly sweeter note and more veg in your soup.)

- Olive oil: 2 tablespoons (if using salt pork or bacon, you can reduce the oil).

- Stock or water: ~8 cups of liquid in total. Ideally use a mix of low-sodium chicken or beef stock and water (for example, 4 cups broth + 4 cups water). Traditional recipes often just use water with a ham hock, which creates its own stock. If you skip the ham hock, using prepared broth will give more flavor.

- Seasonings: 2 bay leaves, 1/2 teaspoon dried red pepper flakes (adjust to taste), 1/4 teaspoon ground black pepper, and salt to taste. (Go easy on salt initially if using a ham hock or salted meats, as they can be salty.) A pinch of cayenne can substitute the red pepper flakes for heat.

- Acid finish: 1–2 tablespoons red wine vinegar or sherry vinegar, or juice of half a lemon. This will be added at the end to brighten the flavor – a modern trick that actually echoes what some Portuguese cooks have done for ages (adding a splash of vinegar or “vinho”).

- Fresh herbs (optional): 2 tablespoons chopped fresh parsley or cilantro for garnish, if desired.

Instructions:

- Prep and (if needed) pre-cook the beans: If using dried beans, plan ahead. Rinse and soak them overnight in plenty of cold water. The next day, drain and place in a large pot with fresh water. If using a ham hock, you can add it in with the beans at this stage. Bring to a boil, then reduce to a gentle simmer. Cook until the beans are tender (about 1 to 1.5 hours). If you added a ham hock, let it simmer with the beans for flavor – skim off any foam that rises. Once done, reserve the cooking liquid as part of your broth and set the beans aside. (If using canned beans, you can skip straight to step 2; you’ll add the drained canned beans later.)

- Brown the meats: In a large heavy-bottomed soup pot (at least 6-quart capacity), heat 2 tablespoons of olive oil over medium heat. If you have diced salt pork or bacon, add it first and let it render for a few minutes until it starts to crisp, then remove any big pieces (you can leave the fat in the pot as cooking oil). Next, add the sliced linguiça/chouriço. Sauté the sausage for about 5 minutes, stirring occasionally, until it begins to brown and release its fat. This step intensifies the sausage flavor by caramelizing it a bit. Optional: Some cooks prefer to brown the sausage separately under a broiler – you can spread the slices on a baking sheet and broil on high for 2–3 minutes to render some fat and brown them, then add to the pot. Either way, once browned, remove the sausage pieces with a slotted spoon and set aside (we will add them back later), leaving the drippings in the pot. (If you used a ham hock in step 1, you can leave it in the pot to continue simmering; otherwise, the flavor from the sausage will suffice.)

- Sauté aromatics: In the same pot with the sausage drippings (add a bit more olive oil if needed), add the chopped onions. Sauté for about 5 minutes on medium heat until the onions are soft and translucent, stirring and scraping up any brown bits from the bottom (those are full of flavor). Add the minced garlic and cook for another 1–2 minutes, being careful not to burn it. If using carrots or tomato paste, add them now and stir for a minute to coat in the oil.

- Build the broth: Pour in your stock and water (e.g., ~8 cups total liquid, including any reserved bean cooking liquid if you cooked dried beans in step 1). If you have a ham hock from earlier, make sure it’s submerged. Add the bay leaves. Increase the heat to bring the soup up to a boil, then immediately reduce to a simmer. Use a spoon to skim off any scum or excess fat that rises to the top in the first few minutes.

- Simmer with kale and potatoes: Add the prepared kale to the pot. It will seem like a lot of greens at first, but kale will soften and cook down significantly. Cover the pot and let the kale simmer for about 10 minutes to begin tenderizing. Then add the potato chunks. (If you have not added any salty meat or stock yet, you can add about 1 teaspoon of salt at this point; otherwise wait and season at the end.) Cover and simmer for another 15–20 minutes. The potatoes should be cooked through and starting to soften on the edges – you can test by piercing one with a knife.

- Add back sausage and beans: Return the browned linguiça/chouriço slices to the pot. Also, add the cooked beans (drained) or canned beans at this stage. Stir everything together. You should now see the beautiful colors of the soup: deep green kale, golden potatoes, reddish sausage and beans. Let the soup continue to simmer on low heat for another 15–20 minutes at least, to let all the flavors mingle. Do not let it boil vigorously – a gentle simmer is best to keep the potatoes intact. If the soup becomes too thick (too crowded with solids), you can add a bit more water or stock to loosen it. Conversely, if it’s too brothy, you can mash a few potato pieces against the side of the pot to thicken the liquid slightly. (Remember, traditional recipes often simmered for hours; if you have time, you can certainly simmer this soup longer. An hour or two of low simmering will only make it better. As one cookbook says, “the longer the soup simmers, the better the flavor”.)

- Season and finish: Taste the soup and add freshly ground black pepper. If it needs salt, add a bit (keeping in mind the sausage and possibly broth already contribute salt). Remove and discard the bay leaves and ham hock (if used) – if there’s any meat on the ham hock, you can shred it and return the meat to the soup. Now for the finishing touch: stir in 1 tablespoon of red wine vinegar (or sherry vinegar). This small burst of acid will brighten the soup significantly. Taste, and add another splash if desired – you want just a subtle tang that lifts the flavors, not an obvious sour taste. (Alternatively, a squeeze of lemon juice can be used for brightness if you prefer that over vinegar.) Many modern Portuguese-American cooks swear by this step to “wake up” the soup at the end, though it’s optional. Finally, sprinkle in the red pepper flakes or cayenne to your heat preference – start with 1/2 teaspoon or so for a gentle warmth. Simmer 5 more minutes.

- Serve: Ladle the Portuguese kale soup into bowls and garnish with fresh parsley if you like. It’s traditional to enjoy it with crusty bread or rolls – try a crusty sourdough, corn bread, or the authentic choice: a slice of Portuguese loaf from a local bakery. In Provincetown, they might serve it with a piece of pumpkin cornbread or a local Portuguese sweet bread on the side. The soup is hearty enough to be a meal on its own, but it also makes a fantastic first course to a seafood feast. As the Lobster Pot demonstrates, it pairs well as a starter to a lobster dinner or clambake.

The Portuguese soup served at the Lobster Pot is far more than a menu item – it’s a story in a bowl. Its history traces back to the Portuguese fishermen who made Provincetown their home over a century ago, bringing with them the rustic soups of their homeland. Over time, kale soup became woven into the fabric of Cape Cod life, earning a place alongside chowder as an emblematic regional dish. At the Lobster Pot, this soup has been dutifully prepared for decades, bridging old and new Provincetown and delighting palettes from around the world. With simple ingredients and a little patience, anyone can recreate this comforting classic and taste a bit of New England Portuguese heritage. As you cook and enjoy Portuguese kale soup – whether at a seaside restaurant or your own kitchen – you participate in a tradition that spans oceans and generations. Bom apetite! Or, as they say on Cape Cod, enjoy – this soup will stick to your ribs and warm your soul.