Rendezvous with the McRib

I don’t eat McDonald’s often. My last serious bout with it was during 2008 when I was a substitute teacher in Brooklyn. Back then, my daily routine included a walk to the nearest Golden Arches for lunch. With only a tight $2 budget, I’d grab a McChicken and a cream of broccoli soup—both just $1 each. It was a cheap, no-frills meal that got me through the day but came with consequences. By summer, I’d gained about 15 pounds and decided it was time to step away. That decision lasted nearly a decade.

Fast forward to my pre-pandemic days, working at a software company with just 30 minutes for lunch. Most days, I packed my own: boiled eggs, or maybe spinach and sardines in olive oil (surprisingly tasty and healthy). But there were mornings I ran out of time, and on those days, McDonald’s was my fallback. My go-to was the Southwest Grilled Chicken Salad—with ranch dressing swapped in for the standard Southwest option. It was surprisingly good and felt like a reasonable indulgence at $6.

Then came winter. And with it, the McRib.

The Nostalgia of the McRib

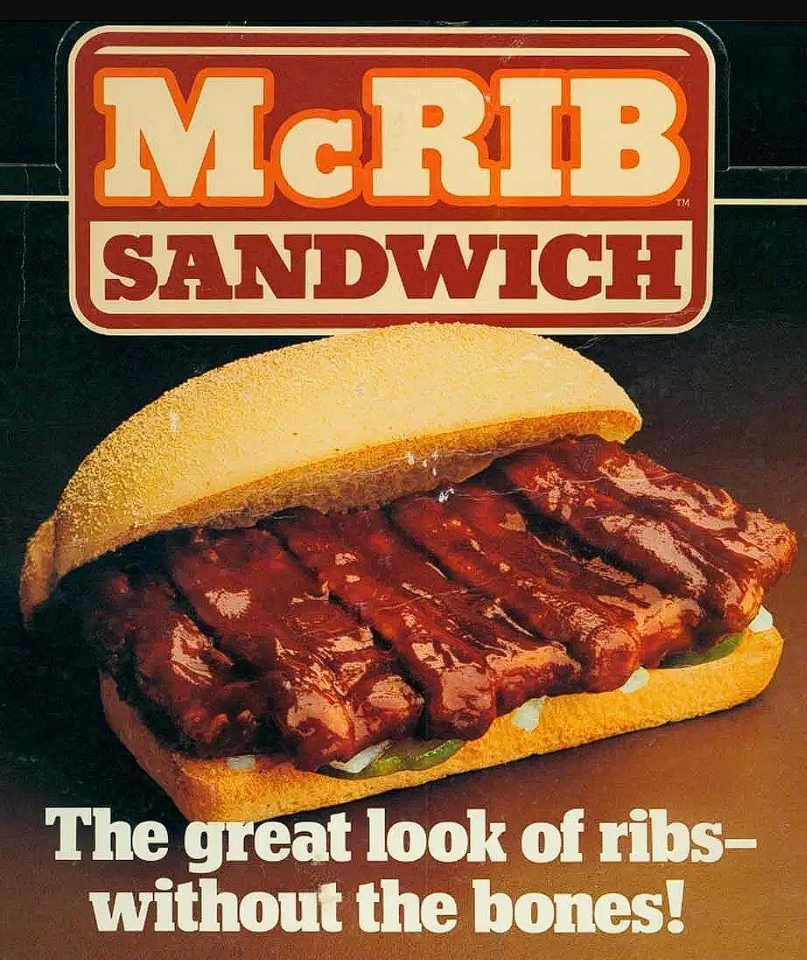

The McRib is a fast-food enigma—rare, fleeting, and surrounded by an almost mythical allure. Introduced in 1981, it wasn’t always the cult favorite it is today. In fact, it initially flopped, earning the unfortunate nickname “McFlop.”

By 1985, it had disappeared from menus. But over time, its limited availability turned it into a phenomenon. Fans track its appearances with the dedication of bird watchers, even creating tools like the McRib Locator app to report sightings. For McDonald’s, this scarcity is intentional—a strategy to heighten demand and make the McRib feel like a rare treasure.

The origins of the McRib are equally fascinating. Its story begins not in a fast-food kitchen but at a military research center in Natick, Massachusetts, in the 1960s. Scientists were tasked with creating palatable meals for soldiers out of inexpensive meat scraps—trimmings, stomach linings, and even hearts. The result? Restructured meat, a method of binding these bits into a more appealing form. This technique later found its way to McDonald’s via Dr. Roger Mandigo, an animal science professor at the University of Nebraska, who refined the process to create a pork patty.

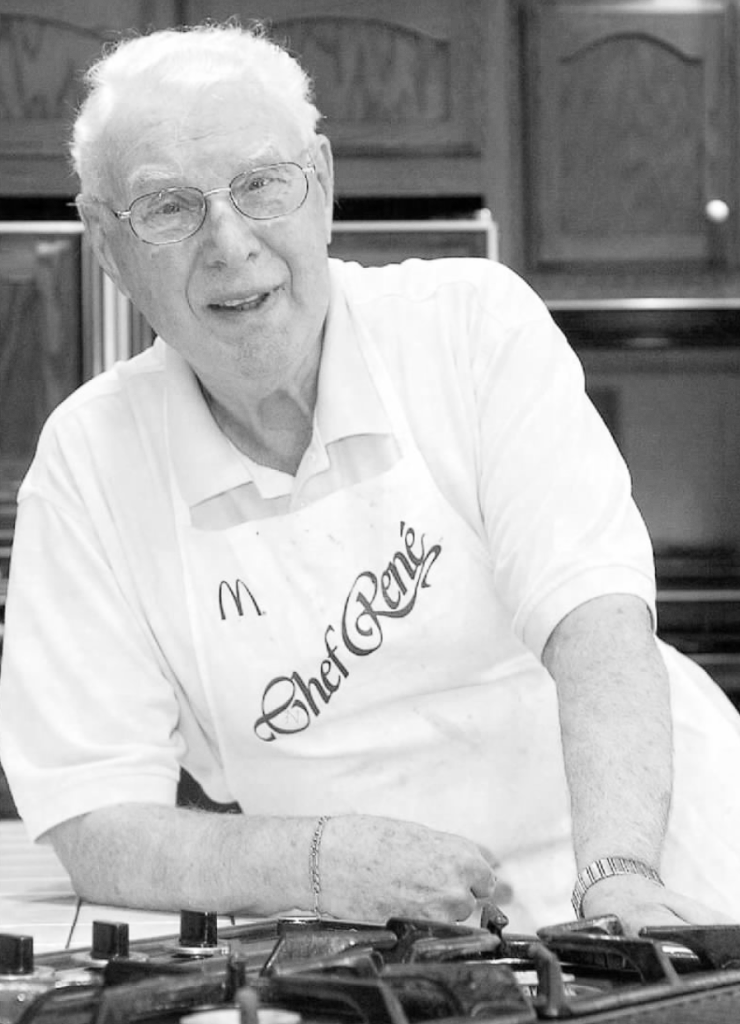

Chef René Arend, a classically trained Luxembourger and McDonald’s first executive chef, then transformed this innovation into the McRib. Inspired by a visit to South Carolina and its iconic pulled pork sandwiches, he insisted the McRib embody true barbecue vibes, complete with a shape mimicking a rack of ribs.

For me, the McRib carries a lot of nostalgia. As a teenager, I loved it. I even tried to recreate it at home:

- A store-bought sub bun.

- On-Cor BBQ rib patties slathered in extra barbecue sauce.

- Pickles and onions.

Was it healthy? Not at all. Did it work? Absolutely.

The McRib also has a fascinating history of comebacks.

After its initial disappearance, it returned sporadically, including a memorable stint in the mid-1990s tied to The Flintstones movie. Its appearances remained erratic, with McDonald’s often pulling it when pork prices rose or when it simply wasn’t selling enough. These vanishing acts only deepened its mystique. By the 2000s, McDonald’s leaned into its cult status, even creating tongue-in-cheek marketing campaigns like the fictional “Boneless Pig Farmers Association of America.” There’s even a McRib Locator, that’s how much people love it.

A Wintery Reunion

Yesterday, driving home from a work meeting, I realized I had no food waiting at home. Then, glowing like a beacon on the snowy horizon, I spotted a McDonald’s. And there it was: a poster announcing the McRib’s return. Nostalgia won. I pulled in, ordered one, and brought it home.

Unwrapping it felt like opening a time capsule. The tangy barbecue sauce, the crunch of pickles and onions, and the soft, somewhat sweet bun—it was all there. The first bite wasn’t the euphoric experience my teenage self remembered, but it was good. Satisfying, even. Once a year, a treat like this feels just right.

The McRib’s composition has sparked endless debates and urban legends. Some claim it contains the same chemical used in gym mats (it doesn’t). The truth? It’s made from boneless pork shoulder, restructured using salt and other additives to bind the meat into its signature rib-like shape. Each patty is seasoned with dextrose (a natural sweetener) and preserved to ensure it stays fresh from production to plate. Is it salty? Absolutely—one sandwich contains 36% of your daily sodium intake. But for a once-a-year indulgence, I can live with that.

The McRib’s scarcity is part of its charm. Whether it’s a marketing ploy, a response to fluctuating pork prices, or both, its sporadic appearances create a sense of urgency. You don’t just eat a McRib—you seize the opportunity.

Will I get another one this season? Probably not. But as I finished the last bite, I couldn’t help but appreciate the strange, storied journey of this sandwich—from military MREs to fast-food legend. The McRib may not be a culinary masterpiece, but it’s a reminder that sometimes, the rarest things in life—no matter how messy or imperfect—are the most memorable.