A Deep Dive Into the History of the American TV Dinner

Growing up in the 1990s, my family rarely relied on TV dinners. My mother, an exceptional cook, made fresh, homemade meals for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. As kids born in the USSR, our diet was very Eastern European, grains like buckwheat and barley, protein dishes like cutlets, shashlyks, and pelmeni, and a lot of salads and sausages. All of which we loved. And of course we ate American food here and there, at school, at friends homes, or just getting take-out every once in a while.

As teenagers, my sister and I were drawn to frozen meals. We found them fascinating—a neatly packaged, self-contained plate that could be heated and ready in minutes. I especially loved how each item sat in its own section: main dish, side, and dessert, all perfectly divided. There was something uniquely satisfying and orderly about it. However weird you might find it, a frozen meal for me, in my childhood, was a treat.

After moving to New York City in my twenties, I rarely touched frozen meals. Affordable, delicious street food and takeout—especially from hole-in-the-wall ethnic eateries—were more enticing than anything from the freezer aisle. But when I returned to Cleveland in 2017 and moved into my own apartment, frozen dinners became a regular staple.

After long days at work, I was thankful to have the convenience of just tossing a Hungry Man into the microwave and having a full meal, albeit filled with sodium, and sometimes soggy vegetables, and kind of weak mashed potatoes. Despite some its downsides, I nevertheless had a warm meal in front of me, steaming, and if you added enough ketchup, or mixed it up with some other stuff in your fridge (for me it was kimchi, or pickles, or a bagged salad), you could really spruce it up.

But how did frozen meals go from novelty to necessity for millions of Americans? The answer lies in a perfect storm of technological innovation, cultural shifts, and a savvy advertising machine that helped rebrand the American dinner.

Freezing Innovation: The Birth of Frozen Foods

Before frozen dinners became a part of American life, freezing food was a tedious and unreliable process. In the early 20th century, the available freezing technology was slow, causing large ice crystals to form inside the food, puncturing cell walls and turning vegetables limp and meat rubbery upon thawing.

The breakthrough came in 1922, thanks to Clarence Birdseye, a naturalist employed by the U.S. government. While working in the Arctic, Birdseye noticed that fish exposed to the region’s intense cold froze almost instantly and retained their fresh texture and taste when thawed. Inspired, he developed a “quick-freezing” process that rapidly froze food between two chilled metal plates, preventing large ice crystals from forming and preserving the food’s structure and flavor.

In 1930, Birdseye began selling frozen vegetables and seafood in Springfield, Massachusetts, but consumers were slow to adopt frozen foods. Most grocery stores lacked freezers, and home refrigeration was still considered a luxury. However, Birdseye persisted, even partnering with appliance manufacturers to design freezers for commercial and home use. By the mid-1930s, he had laid the groundwork for the modern frozen food industry.

Frozen Foods and the Post-War Boom

World War II marked a turning point for frozen food. With canned goods prioritized for soldiers overseas, American households turned to frozen fruits and vegetables out of necessity. The military also adopted frozen meals for long transatlantic flights. Maxson Food Systems created the first pre-packaged frozen dinners for the Navy: three-compartment trays with a meat entrée and two vegetable sides. These meals proved efficient in the skies, but when Maxson attempted to market frozen dinners to civilians after the war, the effort flopped.

However, the war had shifted public perception of convenience foods. By the late 1940s, families sought time-saving products as they adjusted to their new routines in peacetime. This set the stage for Swanson’s breakthrough in 1953: the first mass-marketed “TV dinner.”

The Swanson TV Dinner: A Marketing Masterstroke

The Swanson TV dinner didn’t emerge overnight—it was the result of a series of calculated decisions by a family-run company determined to innovate. Carl Swanson had built Swanson & Sons into a successful food business focused on canned poultry products, but after his death in 1949, his sons Gilbert and Clarke took the company in a bold new direction.

In the early 1950s, the Swanson brothers began producing frozen chicken and turkey pot pies in aluminum trays—a novel concept at the time. But the true breakthrough came in 1953 when a Swanson executive named Gerry Thomas visited a distributor that supplied frozen airline meals. He noticed that the food was packaged in aluminum trays designed to be reheated easily in ovens. Thomas returned to Swanson with a proposal: why not adapt the idea for home use, creating a pre-cooked frozen meal in a tray with three compartments—one for a main dish, two for sides?

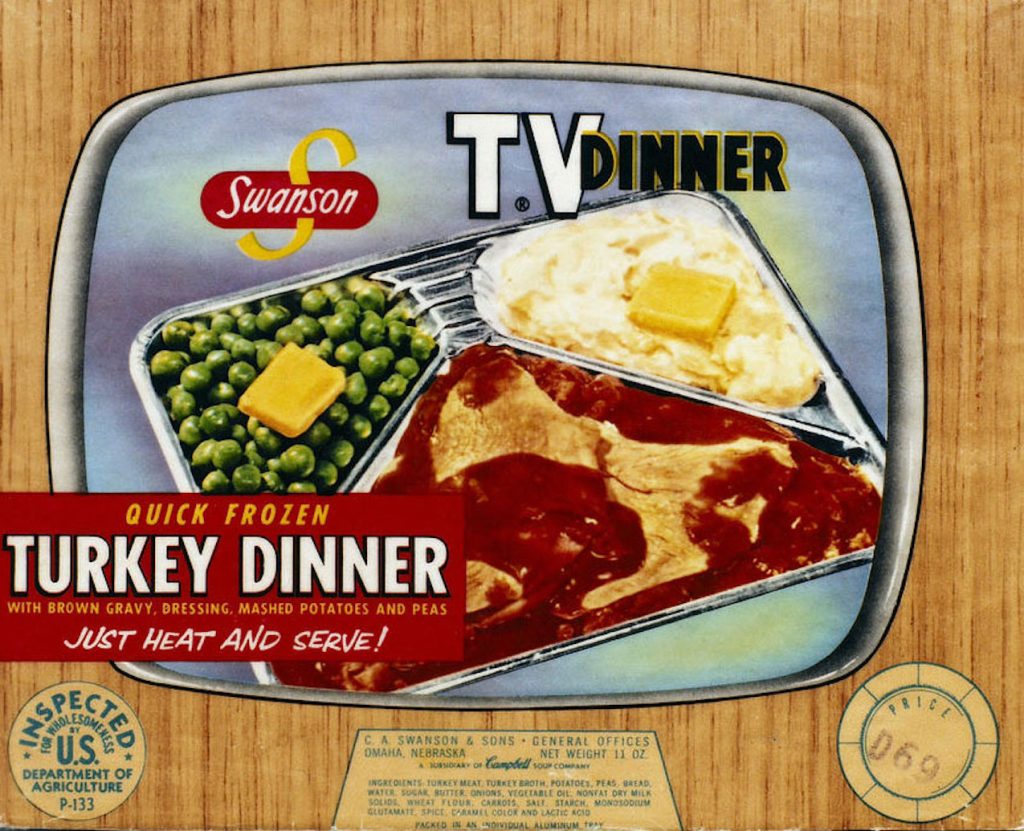

The Swanson brothers ran with the idea, and their first frozen dinner—a Thanksgiving-themed meal of roast turkey, cornbread stuffing, sweet potatoes, and peas—hit store shelves later that year.

The product’s name, “TV Dinner,” was a stroke of marketing genius. By the mid-1950s, over half of American households owned a television, and families were increasingly eating in their living rooms in front of the screen. The branding wasn’t subtle—the package even featured a graphic of a television set, reinforcing the association between Swanson’s frozen meals and prime-time entertainment.

The combination of convenience, novelty, and clever branding was irresistible. Swanson sold 5,000 TV dinners in their first year. By 1954, that number had skyrocketed to 10 million. To keep up with demand, the company phased out its butter and margarine business and focused solely on its poultry-based frozen and canned products. In 1955, Campbell Soup Company acquired Swanson for a major stock deal—a testament to how much value the Swanson brothers had created with their frozen food empire.

Food historian Betty Fussell summed up the appeal: “The segmented tray feels comforting… Everything is in its place, just as we separate foods on our plates when we’re children.” The orderly, three-part layout felt both familiar and novel, inviting customers to feel as though they had a homemade meal—even if it came from the freezer.

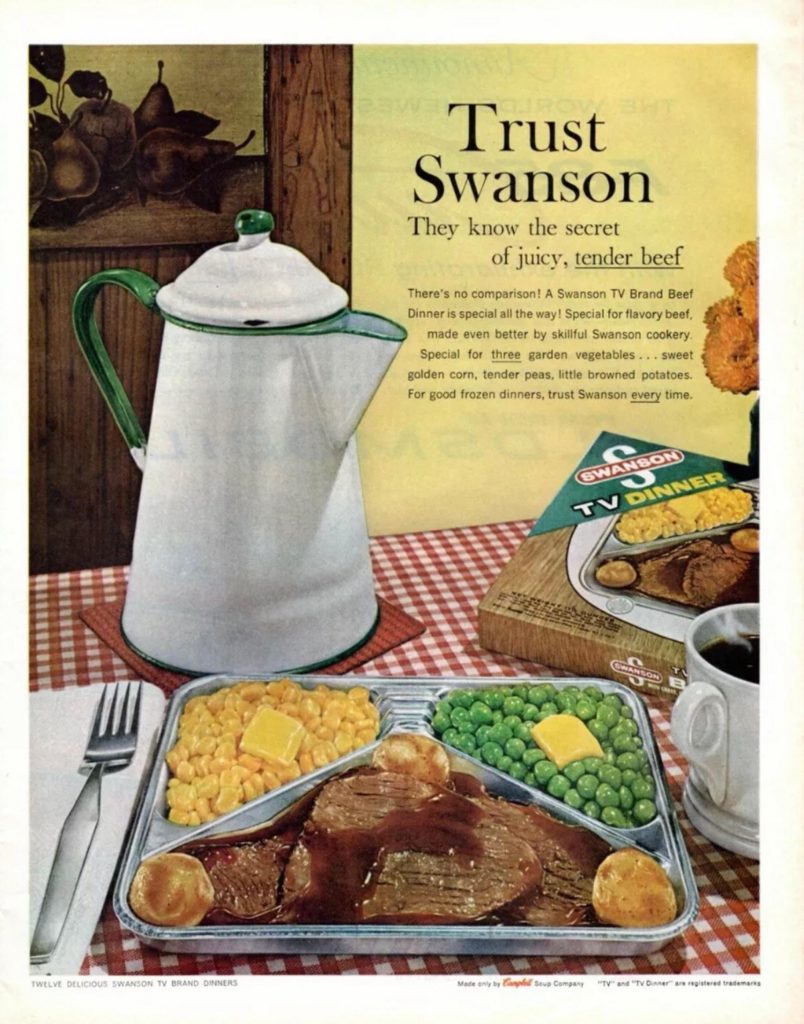

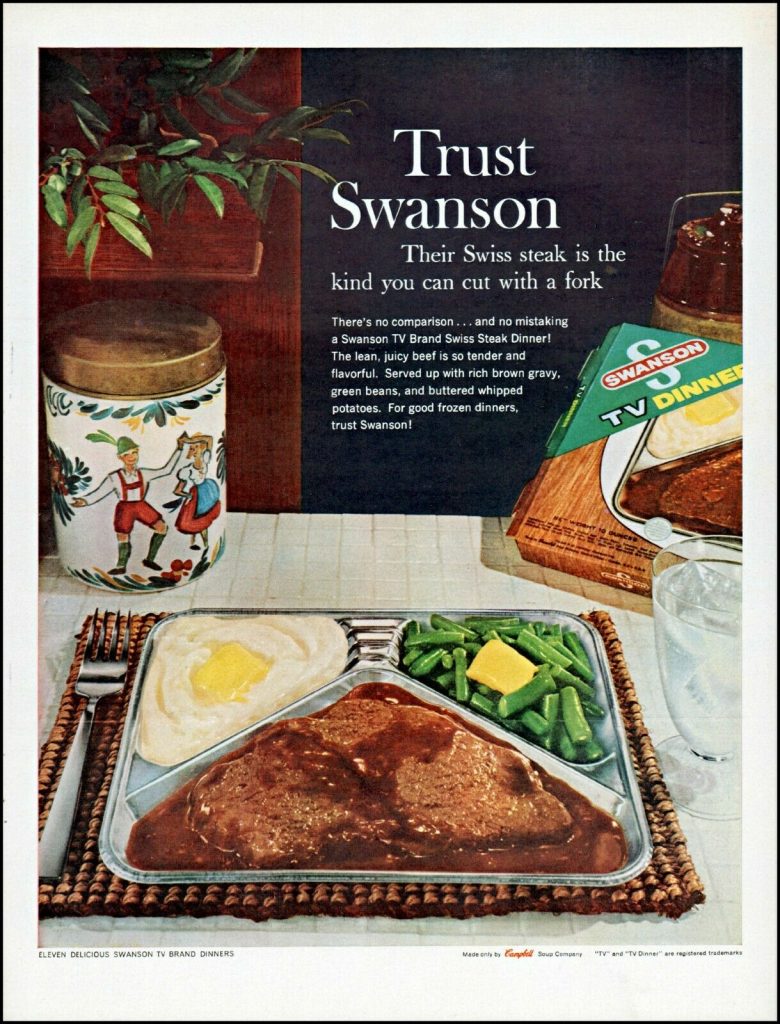

Swanson also leaned into pop culture, sponsoring popular TV shows like The Name’s the Same, further embedding the TV dinner into everyday American life. By 1956, the company was selling 13 million TV dinners annually, solidifying the product as a fixture in households across the country.

The simplicity of the TV dinner resonated with busy families in a post-war world that was embracing modern technology and streamlined routines. What began as an experiment in frozen convenience became a staple of American kitchens—and a defining part of how families ate in front of their screens.

Marketing Convenience: Selling the “Modern” Homemaker

The rise of the TV dinner was about more than just clever advertising—it was about redefining domestic life. Women’s magazines played a crucial role in shaping public attitudes toward frozen meals. Publications like House Beautiful framed TV dinners and home freezers as symbols of modernity and progress for the American housewife.

As post-war prosperity grew, so did consumerism. The ideal 1950s home was stocked with time-saving appliances that promised to lighten the domestic load. In her article for House Beautiful, Florence Paine painted a vivid picture of how women could use frozen food to make life easier while maintaining their husbands’ approval. She suggested that women freeze fresh asparagus at its peak and “convince Dad further that he didn’t make a mistake when he invested in a freezer.”

This anecdote reveals the precarious balancing act women faced in the 1950s: they were expected to adopt modern innovations but remain tethered to their domestic roles. While frozen dinners offered convenience, they did not free women entirely from the expectations of home-cooked meals. Instead, they reframed the work of homemaking as efficient, resourceful, and forward-thinking.

Women’s magazines also framed frozen meals as a luxury of sorts. Articles described freezers as “treasure rooms” filled with a bounty of ready-to-eat meals that could rival the feasts of ancient Roman royalty. By tapping into both practicality and indulgence, advertisers convinced consumers that convenience foods were not just time-savers but status symbols.

The Swanson TV dinner didn’t just change the way people cooked—it redefined how they ate. Instead of gathering around the dinner table, families increasingly ate in front of the television, using TV trays to hold their meals. Television networks quickly noticed this shift, scheduling popular programming during dinner hours to capture family viewership. Advertisers followed suit, targeting entire families with ads for products ranging from soft drinks to household cleaners.

Sociologists observed that this shift in mealtime rituals reflected broader cultural changes. Meals became less about communal bonding and more about individual entertainment. Frozen dinners enabled a level of mealtime independence—each family member could choose their own meal and eat at their own pace, reinforcing the idea of personal preference over collective dining.

By the 1970s, frozen meals had expanded beyond the original turkey dinner to include Salisbury steak, fried chicken, and macaroni and cheese. Swanson’s “Hungry-Man” line catered to consumers who wanted heartier portions, while other brands experimented with ethnic-inspired dishes like enchiladas and stir-fries. However, frozen dinners faced growing criticism for their nutritional content. Many were high in sodium, fat, and preservatives.

In response, health-conscious brands like Lean Cuisine and Healthy Choice emerged in the 1980s, offering low-calorie, portion-controlled frozen meals. Today, the frozen food aisle is more diverse than ever, featuring everything from organic meals to gourmet dishes. Yet even as frozen foods adapt to modern tastes, they continue to evoke a sense of nostalgia for their mid-century origins.

Decades after Swanson’s TV dinners first changed the American dinner table, frozen meals remain a steadfast option for those who need something quick, budget-friendly, and filling. In today’s fast-paced world, TV dinners continue to provide comfort and ease for working parents juggling schedules, young professionals seeking convenience, and retirees who enjoy an easy meal for one. Despite their reputation as simple, utilitarian meals, they’ve taken on a sentimental value, evoking a uniquely American sense of nostalgia.

For many, there’s something reassuring about a full meal packaged into neat, separate compartments. It recalls a time when life felt more structured and familiar, when family members gathered around the TV for dinner and their favorite shows. This cultural nostalgia is so strong that it has inspired restaurant chains like Lazy Dog Restaurant & Bar to recreate the experience of TV dinners—this time with a modern twist.

Lazy Dog has embraced the nostalgia of TV dinners by offering “to-go” versions designed to look like the classic aluminum trays. Their menu includes hearty favorites like BBQ meatloaf with mashed potatoes, fried chicken with country gravy, and cheese enchiladas with Spanish rice and churro cake. The trays aren’t just frozen leftovers—they’re made fresh, packed up, and frozen in-house for diners to take home. For $10.50, customers get a filling meal that feels both retro and homemade.

In 2025, frozen dinners have evolved far beyond the basic meat-and-potatoes fare of the past. New brands and sub-brands from larger companies now offer options that cater to a broader range of dietary preferences and culinary trends. Calorie-conscious meals, vegan and vegetarian entrees, and globally inspired flavors have transformed the frozen food aisle into a more vibrant and diverse space.

Brands like Evol, known for its focus on clean, responsibly sourced ingredients, and Trader Joe’s with its inventive offerings, provide everything from butternut squash-stuffed ravioli to Korean-inspired bulgogi bowls. Frozen food is no longer just about convenience—it’s about exciting, flavorful meals that appeal to more adventurous palates. Italian and Asian fusion dishes, such as tikka masala pasta or spicy miso ramen bowls, have become popular choices, showing that frozen dinners can compete with restaurant-quality takeout.

Despite this reinvention, frozen meals still serve their original purpose: they’re affordable, fast, and comforting. For busy families, they offer a quick dinner option during hectic weeks. For individuals living alone, they provide portion-controlled convenience without sacrificing variety or taste. Health-focused brands now offer grain-free, low-carb, and plant-based options for consumers looking to balance convenience with nutrition.

Even as food culture in 2025 continues to celebrate fresh, farm-to-table dining and meal kits that demand time and preparation, frozen meals continue to hold their ground. Sometimes the greatest luxury is a hot, flavorful dinner that’s ready in minutes. And while many frozen meals now come in sleek biodegradable packaging or eco-friendly microwave trays, they still evoke the same sense of familiarity. Whether it’s an upscale vegan grain bowl or a nostalgic chicken pot pie, there’s a comfort in having a meal neatly divided and ready to enjoy after a long day.

Frozen meals may have started as a mid-century innovation, but their place in modern dining shows that they’ve transcended their practical purpose. They’ve become part of the national story—proof that even something as simple as dinner on a tray can evoke warmth, tradition, and a shared cultural memory.

For me, frozen meals are both a practical solution and a nostalgic nod to my teenage fascination with their tidy compartments. They remind me that even in the age of meal kits and artisanal takeout, there’s something enduring about the appeal of a neatly divided, ready-to-eat dinner. In the end, the TV dinner tells a larger story of how our food choices reflect our cultural priorities—and how even the humblest frozen meal can carry the weight of history.

References:

Dixon Lebeau, M. (2004, November 10). At 50, TV dinner is still cookin’. The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.csmonitor.com/2004/1110/p11s01-lifo.html

Paine, F. (1946, January). You’ll Eat Better with Less Work. House Beautiful, 122.

Paine, F. (1945, January). How Quick Freezing Will Affect Your Future Life. House Beautiful, 53.